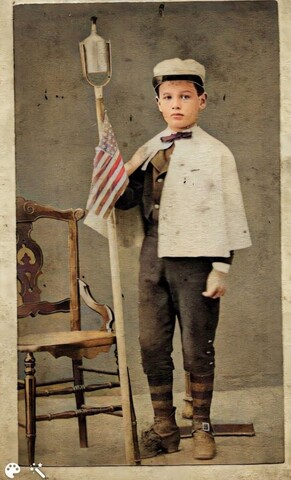

An anonymous boy is suited up for an 1890s political torchlight parade

A couple of years before he died, former President Dwight D. Eisenhower published an informal memoir filled with stories of his early life: At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends (New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1967). As a longtime collector of political campaign memorabilia, I found the passage below of interest.

Writing about his boyhood in Abilene, Kansas, in the 1890s, the future five-star general, World War II hero, and Commander-In Chief shared his first encounter with both marching in formation and a political campaign:

"Somewhere back in that golden time, I had my first experience in a political campaign. I know that some people have always thought that I was not much interested in politics but my debut took place in the fall of 1896, after my entry into grade school. Everybody in school had a button. [Ohio Governor and Republican presidential nominee William] McKinley buttons, bright yellow, predominated because there were few Democrats in the region. Such [Nebraska Congressman and 1896 Democratic presidential nominee William Jennings] Bryan buttons featured the candidate and the figures 16-1.

"Excitement in the town grew rapidly. Many people were concerned about what they called The Gold Standard. Of course this meant nothing to me; I had neither gold nor much concern about it. But it seemed to mean a lot to my elders. Though most of them were of the same party, discussions were both continuous and heated. One evening we learned that a big torchlight parade was to take place.

"Because I was only six, my mother was loath for me to go town to see the parade. Assured by [older Eisenhower brothers] Arthur, now a lordly ten, and Ed, a self-assured eight, that they would take care of me, we started off in the dusk. We were not satisfied to take a place in the middle of the town where the parade would pass. We insisted on going up Buckeye Avenue and into the north end, where it was to start.

"The torches were intriguing. They seemed to be nothing but a rod, and a can of liquid at the end with a wick sticking out. As these were lighted, they threw a smoky flame into the evening air. One was to be carried by each person in the parade, then mustering in a column of fours facing the town. As each torch-lighting took place, it soon became clear that there were more torches than bearers.

"Spying a group of boys standing wide-eyed on the edge of the formation, the parade managers commanded us to come over. We offered no resistance. Each of us was handed a torch and mine was exactly my own height. We were told to shoulder torches, somewhat like shouldering arms. Off we went.

"The town band of a dozen pieces at the head of the procession was supposed to keep us all looking soldierly and marching in cadence. But my short legs presented a problem and the group at the end of the parade was more like a cavorting crowd of lambs. There was a certain amount of disrespectful laughter but we got through the parade in our fashion, with no singed hair and without undoing McKinley. The torches were gathered for return to wherever they had been rented. But my parents missed not only my first appearance in parade formation but my first successful venture into politics. They were among those who were not impressed by the importance of the affair. At least they hadn't taken the trouble to walk the three or four blocks to the parade. It was just as well. There was a tiresome speech underway when my brothers and I took off for home. We wanted to get there before it was too late, for we needed no speeches upon our arrival. Safely concluded, that was one of my few brushes with political life until I found myself drawn into another campaign, half a century later."

Dwight D. Eisenhower, At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends (New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1967), 74-75.

* * * * *